Interview with Joe Richman - Prospector/Self-taught Geology Guy by phone April 12/2020. Reviewed and revised by Joe on May 30/20.

Joe’s Claims

Jeanette: So, you were telling me that you and a buddy have some claims. I’ll just let you tell me something about that.

Joe: Yes, we shared some claims that covered the ground North of the Mine site -the north side of the Stirling Road. My involvement with Stirling goes way back 15 – 20 years maybe. I was working with a different fellow on some rock projects. I picked up the claims, we shared the claims, and he got the claims for the Mine site.

Jeanette: That mine site – as far as I understand, the land is owned by Richmond County. They bought it off a tax sale. That’s what the County Clerk told me.

Joe: I believe that’s true, and the land North of the road, there’s a German fellow.

Jeanette: Norbert.

Joe: Yes, Norbert owns most of the land North of the Stirling Rd. When you do prospecting, you need to get the landowner’s permission to go on their land.

Jeanette: When you have a claim, do you have to put a certain amount of exploration work in every year to be able to keep that claim going?

Joe: Its not really exploration work. You would do more prospecting. It s not exploration at that point it's still a prospector out there with hand tools taking rock samples, and drawing some maps. Exploration would entail more extensive work such as doing geochemical or geophyicial surveys and based on those surveys you may do some drilling later. All this is a long ways away from actual mining, however, based on these findings this may lead to some mining.

Joe: In order to renew it, you have to work on the ground and submit a report, and there’s a certain amount of protocols that have to be met.

Jeanette: I looked into it a little bit one time. I was interested in how that all worked; it seemed like you had to put a bit of money into it or at least some work.

Joe: You get credit for your time. You have to show mapping. You have to show that you actually spent time there. So, there’s a whole system run by the government Department that verifies (this information). Occasionally, it is extremely slow and dysfunctional, but it verifies that you are showing evidence that you did the work that you are claiming to have done.

Jeanette: So, there is accountability to it then.

Jeanette: Do you still have those claims up around where Norbert’s land is?

Joe: Yeah, North of the Stirling Rd. in there on the side of a lake. There were a few years when I spent a lot of time in Stirling. I spent a lot of time on that Mine site. I’m a self-taught Geology guy.

Jeanette: Oh, that's interesting.

Joe's Sculptures/Joe's interest in rocks

Jeanette: I did pop onto your website and quickly took a look at what I call your “rock collection”.

Joe: I call it sculpture.

Jeanette: It’s really interesting. Click here seaducksneedsculpture.com/ to see Joe's rock sculptures.

Jeanette: Did you end up getting any rocks from Stirling?

Joe: No nothing came from Stirling. I use bigger stuff. The ore rocks at Stirling are quite small.

Jeanette: It’s amazing what you did to get them back to your place.

Joe: There’s one that came from near Marble Mountain. Yeah, it costs money. You have to arrange transport, and stuff like that. When I was up in Stirling, it would have been interesting to have a big rock with metal in it. There are some rocks there, smaller rocks, as in a hundred-pound rocks. They would have been good ore in the mining days. They’re just full of metal.

Jeanette: Wendell Holmes, I did an interview with him, and he showed me a rock, it was a small rock, you could put it in your hand but it shows the metal in it and he picked that up when he was working there at the mine.

Jeanette: So, would that have been 1995- 2005 when you were spending time out in Stirling?

Joe: I started chasing rocks in the mid 90’s. So, 1995-2005 that’s a good window for my Stirling work.

Jeanette: And what inspired you to get interested in rocks? What made you get started at it?

Joe: To be honest, it goes back a long way. I immigrated here from the States. When I moved up here I was 25 years old and I’m in the woods and I’m learning how to go fishing. When I look back now, I can see that my brain was also seriously interested in rocks - fascinated. At one point there, when I barely had enough money for food, I was in Halifax, and I went to Dalhousie Bookstore and I chased down a Dalhousie Geology textbook. It cost a ridiculous amount of money for somebody who was broke. That was in the early 70s and that’s just an indication of an innate interest I have had in rocks. It’s a puzzle; Geology is a great puzzle and humans are fascinated by puzzles. The rock puzzle particularly fascinated me, and besides, there’s buried treasure involved and that’s something that also attracts humans. I used to work on the waterfront as a longshoreman and I was surrounded by guys who had the best job in the world, for a blue-collar fellow, you can’t get a better job then working at a Container Terminal. A good many of them were glued to the TV whenever that 'Gold' show would come on. There’s something about buried treasure and sunken treasure, treasure ships; it is definitely attractive to humans. So, there’s always that, when you are chasing rocks; you learn stuff, you try to figure out this puzzle. You figure out where the rocks might go, and there’s always an element of - at the end of it, maybe I’ll be able to find a gold mine.

Joe: At the time I was living in Halifax and I’d go to Stirling on the weekends. So, I‘d have a very focused target when I got there. I was trying to maximize what I could learn in the too short time I had. So as far as the new mill, what I call the new mill, from the 50’s, my focus in that territory was the dumps. There’s a dump to the eastward of the new mill (50's) and I came to understand that was a waste dump and so I would pick through that a lot. There’s a similar place at the south end of the Glory Hole, near the #1 Shaft - near the old shaft - and there’s some glorious rock there.

Jeanette: When you say “glorious” what do you mean by that?

Joe: Very rich as in full of metal.

How Joe became interested in Stirling

Jeanette: What made you think about going to Stirling?

Joe: It was a complete accident. I was working at the time; I was learning how to do field work with one of the Government Geologists. We’d been chasing around different places, mostly around Windsor, Nova Scotia and he was showing me how to do it. I didn’t know anything (about field exploration); I was a fisherman.

I knew nothing of Stirling. I knew nothing of the geology of the Province, and one day the DNR Geologist mentioned Stirling and he said it had been the last base metal mine in the province so, it piqued my curiosity. His office was near the claim’s office, so we just walked over to the claim’s office. There are people who follow claims on a daily basis now by computer but even back then, (when) everything was on paper, there were people who kept track of renewal dates, when certain claims would be coming open. So, claims like Stirling would be a desirable thing to have for somebody who was trying to make a living from that business. He wanted to show me where Stirling was. We hauled out the claims map and the ground appeared to be open. Open means it wasn’t under claim. He was amazed and we asked the fellow who worked for the claims office, “What’s the situation with this; are these claims actually open?” And it seemed that there was some kind of confusion about them. So, as I was there, it cost a pittance to claim them, so I claimed them. I claimed some of them in my name and some in my buddy’s name and in time it turned out they were going to be assigned. Whoever had them before was losing them. They hadn’t fulfilled some protocol, so we wound up with the claims after a period of time. And that was all coincidence. It was all an accident of timing.

Jeanette: I live close by Stirling. I suppose somebody has a claim on that. My great grandfather had a property back there. There was the MacLean’s and then next to that was my great grandfather’s. So when, Thundermin was doing some work, they ran lines all over the place back there. I don’t think they found anything much but anyway they must have the claim on those properties there as well.

Joe: I think they were working ground to the Southwest. They had a target that they thought was worth exploring but as far as I know it came up croppers. They didn’t find enough to keep their interest alive anyway.

Jeanette: I think that company gave some stocks to the property owners in that area.

Joe: At that time (late 1990’s), I tried to talk to miners, sort of like what you have done. I tried to talk to some people who had been underground. I found 3 or 4 different miners. That had been there. I also talked to, I think his name is Richardson, he was the last General Manager. He was still alive in Vancouver.

Jeanette: That was a while ago, then?

Joe: Yeah you’d have to go (back) ten or fifteen years anyway. I think he was 80 something when I talked to him.

Others still interested in Stirling

Joe: When Perry was in Toronto, he made connection with somebody; it’s a small industry and he made connection with somebody who I would call “the tire kicker”, who has an interest in Stirling. It’s at the tire kicking stage. There are people like Doug (Hunter). Doug managed to accumulate a lot of knowledge about Stirling and he spent a lot of time there and he managed to create quite a bit of income, by peddling that knowledge and getting different outfits like Thundermin (involved). It is established that there are numbers for how much metal that is still in the ground at Stirling. And there’s the tailings pond and there’s a certain amount of recoverable metal in it. And then, there was a government geologist, a really good geologist, name of Messervey and he wrote good reports. He was there in the 60’s with a company called “Keltic” and they were doing drilling and exploration, and at some point he wrote a report where he catalogued what he thought was left there in the ground to be recovered.

They are called the “Crown Pillars”. I was never underground, I’m not a miner, I don’t claim any experience there but when you are mining, you have to leave, the same as coal mining, you got to leave pillars, to hold the roof up to keep it from collapsing. And when you are mining metal, the metal in Stirling, in particular, would have been pretty obvious – the good stuff - so there would have been people who were constantly trying to take the good stuff and others who were constantly “slapping their Hands” to keep them from collapsing the mine. But when it was all said and done, at the end of the 50s, there was a certain amount of material – some really rich material, still in the ground around pillars. And so, Messervey, at one point, catalogued what he thought was there. So, in regard to Stirling and people who are interested in Stirling, that’s important information.

Joe: That (Stirling) was a mine that attracted a lot of attention. There was a UCLA professor (Watson) who came up and he actually worked there for two summers doing research and he wrote an extremely concise – 5 or 6-page report about the mine and the mine site and its Geology. Click on the icon below to download this report.

Joe’s Claims

Jeanette: So, you were telling me that you and a buddy have some claims. I’ll just let you tell me something about that.

Joe: Yes, we shared some claims that covered the ground North of the Mine site -the north side of the Stirling Road. My involvement with Stirling goes way back 15 – 20 years maybe. I was working with a different fellow on some rock projects. I picked up the claims, we shared the claims, and he got the claims for the Mine site.

Jeanette: That mine site – as far as I understand, the land is owned by Richmond County. They bought it off a tax sale. That’s what the County Clerk told me.

Joe: I believe that’s true, and the land North of the road, there’s a German fellow.

Jeanette: Norbert.

Joe: Yes, Norbert owns most of the land North of the Stirling Rd. When you do prospecting, you need to get the landowner’s permission to go on their land.

Jeanette: When you have a claim, do you have to put a certain amount of exploration work in every year to be able to keep that claim going?

Joe: Its not really exploration work. You would do more prospecting. It s not exploration at that point it's still a prospector out there with hand tools taking rock samples, and drawing some maps. Exploration would entail more extensive work such as doing geochemical or geophyicial surveys and based on those surveys you may do some drilling later. All this is a long ways away from actual mining, however, based on these findings this may lead to some mining.

Joe: In order to renew it, you have to work on the ground and submit a report, and there’s a certain amount of protocols that have to be met.

Jeanette: I looked into it a little bit one time. I was interested in how that all worked; it seemed like you had to put a bit of money into it or at least some work.

Joe: You get credit for your time. You have to show mapping. You have to show that you actually spent time there. So, there’s a whole system run by the government Department that verifies (this information). Occasionally, it is extremely slow and dysfunctional, but it verifies that you are showing evidence that you did the work that you are claiming to have done.

Jeanette: So, there is accountability to it then.

Jeanette: Do you still have those claims up around where Norbert’s land is?

Joe: Yeah, North of the Stirling Rd. in there on the side of a lake. There were a few years when I spent a lot of time in Stirling. I spent a lot of time on that Mine site. I’m a self-taught Geology guy.

Jeanette: Oh, that's interesting.

Joe's Sculptures/Joe's interest in rocks

Jeanette: I did pop onto your website and quickly took a look at what I call your “rock collection”.

Joe: I call it sculpture.

Jeanette: It’s really interesting. Click here seaducksneedsculpture.com/ to see Joe's rock sculptures.

Jeanette: Did you end up getting any rocks from Stirling?

Joe: No nothing came from Stirling. I use bigger stuff. The ore rocks at Stirling are quite small.

Jeanette: It’s amazing what you did to get them back to your place.

Joe: There’s one that came from near Marble Mountain. Yeah, it costs money. You have to arrange transport, and stuff like that. When I was up in Stirling, it would have been interesting to have a big rock with metal in it. There are some rocks there, smaller rocks, as in a hundred-pound rocks. They would have been good ore in the mining days. They’re just full of metal.

Jeanette: Wendell Holmes, I did an interview with him, and he showed me a rock, it was a small rock, you could put it in your hand but it shows the metal in it and he picked that up when he was working there at the mine.

Jeanette: So, would that have been 1995- 2005 when you were spending time out in Stirling?

Joe: I started chasing rocks in the mid 90’s. So, 1995-2005 that’s a good window for my Stirling work.

Jeanette: And what inspired you to get interested in rocks? What made you get started at it?

Joe: To be honest, it goes back a long way. I immigrated here from the States. When I moved up here I was 25 years old and I’m in the woods and I’m learning how to go fishing. When I look back now, I can see that my brain was also seriously interested in rocks - fascinated. At one point there, when I barely had enough money for food, I was in Halifax, and I went to Dalhousie Bookstore and I chased down a Dalhousie Geology textbook. It cost a ridiculous amount of money for somebody who was broke. That was in the early 70s and that’s just an indication of an innate interest I have had in rocks. It’s a puzzle; Geology is a great puzzle and humans are fascinated by puzzles. The rock puzzle particularly fascinated me, and besides, there’s buried treasure involved and that’s something that also attracts humans. I used to work on the waterfront as a longshoreman and I was surrounded by guys who had the best job in the world, for a blue-collar fellow, you can’t get a better job then working at a Container Terminal. A good many of them were glued to the TV whenever that 'Gold' show would come on. There’s something about buried treasure and sunken treasure, treasure ships; it is definitely attractive to humans. So, there’s always that, when you are chasing rocks; you learn stuff, you try to figure out this puzzle. You figure out where the rocks might go, and there’s always an element of - at the end of it, maybe I’ll be able to find a gold mine.

Joe: At the time I was living in Halifax and I’d go to Stirling on the weekends. So, I‘d have a very focused target when I got there. I was trying to maximize what I could learn in the too short time I had. So as far as the new mill, what I call the new mill, from the 50’s, my focus in that territory was the dumps. There’s a dump to the eastward of the new mill (50's) and I came to understand that was a waste dump and so I would pick through that a lot. There’s a similar place at the south end of the Glory Hole, near the #1 Shaft - near the old shaft - and there’s some glorious rock there.

Jeanette: When you say “glorious” what do you mean by that?

Joe: Very rich as in full of metal.

How Joe became interested in Stirling

Jeanette: What made you think about going to Stirling?

Joe: It was a complete accident. I was working at the time; I was learning how to do field work with one of the Government Geologists. We’d been chasing around different places, mostly around Windsor, Nova Scotia and he was showing me how to do it. I didn’t know anything (about field exploration); I was a fisherman.

I knew nothing of Stirling. I knew nothing of the geology of the Province, and one day the DNR Geologist mentioned Stirling and he said it had been the last base metal mine in the province so, it piqued my curiosity. His office was near the claim’s office, so we just walked over to the claim’s office. There are people who follow claims on a daily basis now by computer but even back then, (when) everything was on paper, there were people who kept track of renewal dates, when certain claims would be coming open. So, claims like Stirling would be a desirable thing to have for somebody who was trying to make a living from that business. He wanted to show me where Stirling was. We hauled out the claims map and the ground appeared to be open. Open means it wasn’t under claim. He was amazed and we asked the fellow who worked for the claims office, “What’s the situation with this; are these claims actually open?” And it seemed that there was some kind of confusion about them. So, as I was there, it cost a pittance to claim them, so I claimed them. I claimed some of them in my name and some in my buddy’s name and in time it turned out they were going to be assigned. Whoever had them before was losing them. They hadn’t fulfilled some protocol, so we wound up with the claims after a period of time. And that was all coincidence. It was all an accident of timing.

Jeanette: I live close by Stirling. I suppose somebody has a claim on that. My great grandfather had a property back there. There was the MacLean’s and then next to that was my great grandfather’s. So when, Thundermin was doing some work, they ran lines all over the place back there. I don’t think they found anything much but anyway they must have the claim on those properties there as well.

Joe: I think they were working ground to the Southwest. They had a target that they thought was worth exploring but as far as I know it came up croppers. They didn’t find enough to keep their interest alive anyway.

Jeanette: I think that company gave some stocks to the property owners in that area.

Joe: At that time (late 1990’s), I tried to talk to miners, sort of like what you have done. I tried to talk to some people who had been underground. I found 3 or 4 different miners. That had been there. I also talked to, I think his name is Richardson, he was the last General Manager. He was still alive in Vancouver.

Jeanette: That was a while ago, then?

Joe: Yeah you’d have to go (back) ten or fifteen years anyway. I think he was 80 something when I talked to him.

Others still interested in Stirling

Joe: When Perry was in Toronto, he made connection with somebody; it’s a small industry and he made connection with somebody who I would call “the tire kicker”, who has an interest in Stirling. It’s at the tire kicking stage. There are people like Doug (Hunter). Doug managed to accumulate a lot of knowledge about Stirling and he spent a lot of time there and he managed to create quite a bit of income, by peddling that knowledge and getting different outfits like Thundermin (involved). It is established that there are numbers for how much metal that is still in the ground at Stirling. And there’s the tailings pond and there’s a certain amount of recoverable metal in it. And then, there was a government geologist, a really good geologist, name of Messervey and he wrote good reports. He was there in the 60’s with a company called “Keltic” and they were doing drilling and exploration, and at some point he wrote a report where he catalogued what he thought was left there in the ground to be recovered.

They are called the “Crown Pillars”. I was never underground, I’m not a miner, I don’t claim any experience there but when you are mining, you have to leave, the same as coal mining, you got to leave pillars, to hold the roof up to keep it from collapsing. And when you are mining metal, the metal in Stirling, in particular, would have been pretty obvious – the good stuff - so there would have been people who were constantly trying to take the good stuff and others who were constantly “slapping their Hands” to keep them from collapsing the mine. But when it was all said and done, at the end of the 50s, there was a certain amount of material – some really rich material, still in the ground around pillars. And so, Messervey, at one point, catalogued what he thought was there. So, in regard to Stirling and people who are interested in Stirling, that’s important information.

Joe: That (Stirling) was a mine that attracted a lot of attention. There was a UCLA professor (Watson) who came up and he actually worked there for two summers doing research and he wrote an extremely concise – 5 or 6-page report about the mine and the mine site and its Geology. Click on the icon below to download this report.

| watson_1957[6614].pdf |

Richardson, the man I mentioned, the General Manager, he wrote the best three pages on Stirling Mine that I’ve ever seen. Very concise (information) about the Geological review of everything. click on the icon below to download this report. To rotate the page click on first button on the top right of screen. To fit to page click twice on the first button on the lower right part of the screen.

| richardson.pdf |

Joe: That’s why rocks are such a puzzle. They are a good puzzle because very smart people look at things and they think they can figure them out and invariably they can’t, but they try, and they’ll write a report about “This is how it is”. Until something actually gets opened up, it’s really hard to tell, and even then, it can be hard to tell. There’s a PHD who used to work for the government here, Kontak, have you come across him?

Jeanette: No

Joe: He spent a good part of his career studying Stirling. Nobody has ever figured out the geology there. It is very complex.

Joe: Another name I came across is of a miner who was living in Ontario. He worked at Stirling and then he went to NFLD. He told me a funny story. He was underground at Stirling, where he started as a kid. So, he learned his trade and when Stirling was over, he took his trade and his skill set and he went to NFLD where there was still mining going on and he made a living there for years. Then he went to Ontario and he worked, I think, in the Sudbury area. I had known that Stirling was very wet underground, it was known as a very wet mine and buddy said that he was at Stirling, he was in NFLD and then he went to Ontario. He said, “It wasn’t until I got to Ontario that I found out that there was such a thing as 'grout'.” 'Grout' is something that in a well run mine, is used to stop the water. You put grout – and it is called grout for a reason - in the cracks; in order to make the underground fit to work in, otherwise, like at Stirling, you are constantly being rained on.

Jeanette: Yes, in some of the stories they were telling me about the water.

Joe: That’s no way to effectively spend 8-12 hours. It’s a misery for no reason.

Death from a rock fall

Joe: I talked to a fellow, who was underground there (Stirling) for a relatively short period of time. I think it was for a summer or a year. He had been studying Mining Engineering at Dal Tech, so he thought this was going to be his career. Stirling was going on, so he went there. It was an obvious career move, to take his engineering education and work underground. He was working next to a guy one day, and the fella died – instantaneously killed. A rock fell on his head. That metal rock is amazingly heavy, and the rock fell from the roof onto his head and killed him. And at that moment, that young guy, who was going to be a Mining Engineer, changed his career.

Jeanette: That’s interesting because I’m trying to find out who the people who died in the mine were. There were two guys, who died down in the mine, in the 50’s. I don’t know who they are, but (I understand) it was a rock fall. This guy would be able to tell me who it was. So, what was his name?

Joe: I’ll have to track it down. He went from Mining Engineering to Health. He spent the next 30 years of his life in health. He may be still alive.

Joe: I went through all the reports that had been written about the place and I spent a lot of time digging on the site, trying to locate things that were shown on maps, and I had pretty good luck with that.

Talc

Joe: When they got down so deep, in the ‘main Zone’ of the mine, they ran into Talc. Talc is very unstable. It’s not strong rock. It crumbles easily so it is very dangerous to mine around it. When they got down to around the 8th level, roughly 800 feet deep. The amount of Talc in amongst the ore, increased drastically, and I think that might be part of the reason why they quit mining. It had become very dangerous and very expensive to keep mining. Money dictates everything so that was definitely a complication in the latter stages of the mine.

Raises

Joe: There’s a couple of diggings, they may be 10-20 meters wide on the current surface at the mine site, and they narrow down, they may be only a few meters deep. They were what you would call “raises”. They were holes that came up from the mining stopes to the surface, and they broke through the surface rock. All mines have things like these raises. They are one way to get air into the mine. They are often made by accident in older mines; when they are following up the metal they go too far, and the roof falls in on them. If it just falls in a little bit, then they have a sky hole but if you are up at the surface, they’re very dangerous. If you fell in one, you could go down a hundred feet or maybe more than that. So, the government went there a number of years ago and they capped two of them. It may have been the same time they put that stainless-steel grid over the Shaft 2 hole.

Jeanette: Yeah, I think it was at the same time, that’s part of the recapping project. There’s a link to that (on the website) They capped the two shafts #1 & #2, and the two raises (using different methods). Click here novascotia.ca/natr/meb/pdf/96ofr18.asp to access this site).

Joe: The reason I mention it, the one raise that was closest to the #2 shaft, it’s got an outcrop, of amazing rock. If you look at it, it will look like uninteresting black rock. My memory is that it is a kind of rounded outcrop. An outcrop is not loose boulders, it’s not surface rock. It is rock that is connected, let’s say, to the center of the earth. And this particular outcrop is a kind of rounded thing. It might be 2 x 2 meters. If you took a hammer to it, broke a piece of it, it’s just full of metal. One way to know if you have ore is – not only is it shiny, but for the size of it, it is extremely heavy and that will tell you. Metal is three times as heavy as rock.

Jeanette: That’s interesting, that rock that Wendell showed me, I put it in my hand. It was very heavy and that’s what he said about it - because it had metal in it, it was very heavy.

Dept of Mines/Messervey

Jeanette: You were talking about Messervey before. In some of the pictures from back in the 20’s on the Government website and Gold.com, there is a Messervey, he may be the same guy. He is credited for the photographs. Click here novascotiagold.ca/theme/exploitation_de_lor-mining/capebreton-eng.php to see these photos.

Jeanette: I wonder if that would be the same guy.

Joe: It would be the same guy. He was a big deal in the Dept of Mines.

Jeanette: No

Joe: He spent a good part of his career studying Stirling. Nobody has ever figured out the geology there. It is very complex.

Joe: Another name I came across is of a miner who was living in Ontario. He worked at Stirling and then he went to NFLD. He told me a funny story. He was underground at Stirling, where he started as a kid. So, he learned his trade and when Stirling was over, he took his trade and his skill set and he went to NFLD where there was still mining going on and he made a living there for years. Then he went to Ontario and he worked, I think, in the Sudbury area. I had known that Stirling was very wet underground, it was known as a very wet mine and buddy said that he was at Stirling, he was in NFLD and then he went to Ontario. He said, “It wasn’t until I got to Ontario that I found out that there was such a thing as 'grout'.” 'Grout' is something that in a well run mine, is used to stop the water. You put grout – and it is called grout for a reason - in the cracks; in order to make the underground fit to work in, otherwise, like at Stirling, you are constantly being rained on.

Jeanette: Yes, in some of the stories they were telling me about the water.

Joe: That’s no way to effectively spend 8-12 hours. It’s a misery for no reason.

Death from a rock fall

Joe: I talked to a fellow, who was underground there (Stirling) for a relatively short period of time. I think it was for a summer or a year. He had been studying Mining Engineering at Dal Tech, so he thought this was going to be his career. Stirling was going on, so he went there. It was an obvious career move, to take his engineering education and work underground. He was working next to a guy one day, and the fella died – instantaneously killed. A rock fell on his head. That metal rock is amazingly heavy, and the rock fell from the roof onto his head and killed him. And at that moment, that young guy, who was going to be a Mining Engineer, changed his career.

Jeanette: That’s interesting because I’m trying to find out who the people who died in the mine were. There were two guys, who died down in the mine, in the 50’s. I don’t know who they are, but (I understand) it was a rock fall. This guy would be able to tell me who it was. So, what was his name?

Joe: I’ll have to track it down. He went from Mining Engineering to Health. He spent the next 30 years of his life in health. He may be still alive.

Joe: I went through all the reports that had been written about the place and I spent a lot of time digging on the site, trying to locate things that were shown on maps, and I had pretty good luck with that.

Talc

Joe: When they got down so deep, in the ‘main Zone’ of the mine, they ran into Talc. Talc is very unstable. It’s not strong rock. It crumbles easily so it is very dangerous to mine around it. When they got down to around the 8th level, roughly 800 feet deep. The amount of Talc in amongst the ore, increased drastically, and I think that might be part of the reason why they quit mining. It had become very dangerous and very expensive to keep mining. Money dictates everything so that was definitely a complication in the latter stages of the mine.

Raises

Joe: There’s a couple of diggings, they may be 10-20 meters wide on the current surface at the mine site, and they narrow down, they may be only a few meters deep. They were what you would call “raises”. They were holes that came up from the mining stopes to the surface, and they broke through the surface rock. All mines have things like these raises. They are one way to get air into the mine. They are often made by accident in older mines; when they are following up the metal they go too far, and the roof falls in on them. If it just falls in a little bit, then they have a sky hole but if you are up at the surface, they’re very dangerous. If you fell in one, you could go down a hundred feet or maybe more than that. So, the government went there a number of years ago and they capped two of them. It may have been the same time they put that stainless-steel grid over the Shaft 2 hole.

Jeanette: Yeah, I think it was at the same time, that’s part of the recapping project. There’s a link to that (on the website) They capped the two shafts #1 & #2, and the two raises (using different methods). Click here novascotia.ca/natr/meb/pdf/96ofr18.asp to access this site).

Joe: The reason I mention it, the one raise that was closest to the #2 shaft, it’s got an outcrop, of amazing rock. If you look at it, it will look like uninteresting black rock. My memory is that it is a kind of rounded outcrop. An outcrop is not loose boulders, it’s not surface rock. It is rock that is connected, let’s say, to the center of the earth. And this particular outcrop is a kind of rounded thing. It might be 2 x 2 meters. If you took a hammer to it, broke a piece of it, it’s just full of metal. One way to know if you have ore is – not only is it shiny, but for the size of it, it is extremely heavy and that will tell you. Metal is three times as heavy as rock.

Jeanette: That’s interesting, that rock that Wendell showed me, I put it in my hand. It was very heavy and that’s what he said about it - because it had metal in it, it was very heavy.

Dept of Mines/Messervey

Jeanette: You were talking about Messervey before. In some of the pictures from back in the 20’s on the Government website and Gold.com, there is a Messervey, he may be the same guy. He is credited for the photographs. Click here novascotiagold.ca/theme/exploitation_de_lor-mining/capebreton-eng.php to see these photos.

Jeanette: I wonder if that would be the same guy.

Joe: It would be the same guy. He was a big deal in the Dept of Mines.

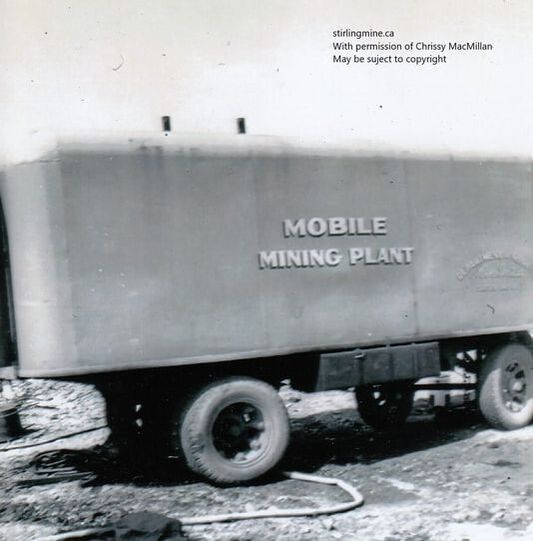

In the 50’s, he had a prominent position. He was a smart guy. He was a good geologist. He was a doer. He was involved in pumping out the glory hole. At that time, in the 1950’s, the government ran their own drilling crew. He set up this thing called the Mobile Mining Plant.

Joe: That was his work. He believed that they should have their own crew of people who were independent of private industry that could go around and advance projects. I don’t know what you know of the mining industry, but the idea in general is to take on something like Doug (Hunter) took on in Stirling and advance them. You get them to a further point, closer toward becoming something of value. Even if a mine happens, there’s 20 years in the making, at least. And you have to take something from its discovery, and you have to find out enough about it to attract enough interest, to attract the money to properly investigate it, and continually try to advance the project, and make it more interesting for somebody richer or bigger or more powerful to try to find the actual deposit. The reason people do this, most of them do it for money, and the big money is in identifying a resource. It’s worth a lot of money. So when you are sitting in Cape Breton, if you had a billion dollars, sitting on top of the highlands, and you could get past all the road blocks, in developing that, that billion dollars would filter down all over Cape Breton – and Mainland Nova Scotia. That’s the reason Mining companies come in and spend big amounts of money to do something because at the end of the road, if you are smart enough and lucky enough, you find a very large blueberry pie and there are slices for everybody.

Jeanette: So, the Dept of Mines, that was another mystery. (I was wondering) why they were the ones doing all the pumping out of the mine. They had set up a few small buildings there. I Interviewed women who worked in the cookhouse and one of the ladies married Johnny MacMillan. He was one of the guys who was actually pumping out the Glory Hole. I was wondering why they put all this effort into this. So, they were one of those groups – they thought (their work) was going to benefit the Province of Nova Scotia by having a mine.

Joe: Yes, and it did, in the short term it did. And it made for a lot of jobs in a very rural area lacking in economic opportunities.

Jeannette: It employed a lot of people.

Joe: By pumping out the 1930’s mine, they were trying to attract private companies to come in and finish what was left in the ‘30s and “the private money” obviously didn’t see enough excuse to invest the first money. The first money would have been to pump the mine out. So that was Messervey’s whole idea as a high level government overseer - if we have this group of people who work for us - they ‘re trained - they know what they are doing; they can do it as cheaply and as effectively as anybody and we can send them to Stirling for a start. There were other places they worked. I think Stirling was the biggest and most prominent. They pumped the mine out. It goes back to the puzzle. You have all these reports, and they tell you what someone thinks is under there, but you don’t really know what’s under there. And in the Stirling case, there was a Glory Hole, and if you had scuba tanks you could swim through it but you still couldn’t see what was going on there. And, you don’t really trust reports because the industry is driven by big money, so reports are often exaggerated.

Joe: The government invested a certain amount of money to pump that mine out and they proved Messervey’s story. They pumped the mine out, Dome came in, cataloged what they could see, and they decided to open the mine, making a lot of jobs; that’s the game from the public’s point of view -jobs.

Jeanette: So, their interest in that was getting people working.

Jeanette: On my interview page, there’s one letter from a McCrea fellow. He met up with my brother. He was an Engineer. His father was the president of Dome Petroleum. So, he talks about the Talc and a lot of other stuff and his brother did a thesis as well. You might find that interesting story.

The Glory Hole/Glory Rock

Jeanette: About the Glory hole, was it something that was excavated in the 20’s?. Was it a shaft that collapsed?

Joe: Not a shaft. It was a ceiling collapsed. They got too close to the surface above a stope.

Joe: You have a picture of the Glory hole pumped out. I have a picture somewhere that shows a fissure, it’s a slit. It must have been just after they broke through the thing,. It’s a long slit in the ground with a wooden fence around it. That would be from back in the 20’s or 30’s. Then, my understanding was, they brought in a steam shovel in the ‘50s and that’s and that’s what took the thing from being a little slit of a roof collapse to this huge, much bigger hole. They did that with a steam shovel.

Jeanette: Why were they digging into that?

Joe: That was the richest stuff. It’s called a Glory Hole for a reason. That was the richest stuff there was. And that’s why they would have taken it - you have to think about these guys climbing up from below on wooden scaffolding, picking away at rock, drilling rock. I mean it was back in the 30’s; it wasn’t good conditions. It would have been horrible conditions. They would have had a waterfall raining on them straight time. And why are they doing it, because the rock is so rich you can’t help but take it. It’s Glory rock. And they went a little too far and the roof of the cathedral collapsed on them. And, maybe somebody gets hurt, and maybe somebody dies, but there’s a hole through to the sky.

There likely a similar situation, if you go on the land south of the Glory Hole and the Shaft 1. There was an old woods road and beside that, there was a collapse too. When you walk to the Southern and you look west of this southern bound log road, there’s a depression, presumably, a collapse. When they mined a little bit in that direction, they again got a little too close to the ceiling and that’s likely what that collapse is. Nobody’s been underground since to verify that but that’s most likely what that is.

Joe: I was trying to find these Glory spots, of surface ore, that were identified on some of the old maps. What they would have done, at some point early on – they were constantly walking the site. The original discovery was in the creek; there was a copper showing in the creek. And then, as time went on, they mapped near by going out further and further, 15 meters, 50 meters, 100 meters. They would have mapped other places- there’d be people digging holes by hand and finding rock of some value. And that’s how you start a mine project. You expose everything you can at surface, because it is a whole lot cheaper than exposing it underground. So, they walked around, and they exposed these spots, these isolated spots, of really good stuff at the surface. Because I didn’t have machinery to play with, I was trying to locate things that I could expose by shovelling by hand and I found one or two of them. We’re talking about stuff that is 30% metal. That’s just unbelievably rich rock. These days base metal ore would run 3% metal or something like that, so you’re talking about something that is 10X’s richer. That’s amazingly rich rock so, I was spending time up there, trying to find buried treasure. And I thought it was going to put money in my pocket. It didn’t, but that was some of the dream, as well.

The Tailings Pond

Joe: There was a company “Seabright” that was there in the 70’s. They catalogued the tailings pond. They surveyed the tailings pond, and took samples on a grid laid out on the tailings pond, and produced a report that said that there was this much metal, this much gold, in the tailings pond to be recovered. From that report, it’s been believed ever since, there’s 20,000 ounces of gold in those tailings. And where did those tailings come from? Richardson told me they didn’t flatten the ground, that that was too much hard work for no gain. They just ran their tailings out over the natural landscape, and the tailings would have been coming, in their case, out of another pipe that came out from the mill. One way of trapping metal is from the ground up ore. They use chemicals to grab on to the good stuff. And the waste, the tailings, is fluid, and it can be pumped through a pipe. They had created this earthen dam around an area they thought would be big enough to hold the tailings that would be produced, and they ran the pipe into the side of that. It would have been on the Western side of the currently existing tailings pond.

The old mill(1920s/1930’) didn’t have a tailings pond - that was ‘the bad old days’; they didn’t attempt to protect the ground at all. So, they pumped directly into the brook and that’s what killed all the vegetation along the brook because those tailings are very high in acid. And I was told by somebody local, that it killed everything for quite a way downstream. ‘Old ways” aren’t necessarily good – or, best.

Jeanette: Yes, that brook - it’s called Strachan’s brook. It goes all the way down though Framboise, crosses the road twice. It passes through land once owned by Strachan’s (thus the name) before going into the Framboise River which empties into the Ocean. It killed all the vegetation all the way down. When I was a kid there was a vast area of sand where it crossed the Barron road (aka Three Rivers road).

In the 50’s they made the tailings pond. If it rained a lot the water could flow into the river, so they had a culvert there. It was supposed to settle, (and the excess water would drain into the brook) but over the years the sediment ended up getting under the culvert and going into the brook, until 20 years ago then the government did another project there. Click here novascotia.ca/natr/meb/data/pubs/ofr_me_1996-016.pdf to view this project.

Joe: I was told, the last time I was there, by somebody local, that he had seen the first sign of green, starting to grow back. Between the tailings pond and the ocean. It took 50 years– the acid had been diluted enough that finally something could grow.

Joe: To me it’s a horror story in one sense but in the other sense 50 years in the history of this planet isn’t very long. It's only taken fifty years for all the poisons/toxins. that went into that brook, to be neutralized. There was a certain amount of talc and limestone with the ore, and Limestone and talc would neutralize the very acid metal minerals that contained the metal.

Jeanette: And same with the tailings pond, all that stuff is there, still. There’s still lots of chemicals in that stuff. Anyways, it’s not gone but it is contained for the most part.

Joe: It’s contained. That’s a good way of thinking of it. And sunlight, time and neutralizers go to work. I can take some hopefulness from that.

I give Jeanette Strachan permission to use the above information in part or in whole, online or in print If for publication I retain the right to review again the material to be used and the nature of the publication.

Signed by Joe Richman on May 30/20 with the above condictions.

Jeanette: So, the Dept of Mines, that was another mystery. (I was wondering) why they were the ones doing all the pumping out of the mine. They had set up a few small buildings there. I Interviewed women who worked in the cookhouse and one of the ladies married Johnny MacMillan. He was one of the guys who was actually pumping out the Glory Hole. I was wondering why they put all this effort into this. So, they were one of those groups – they thought (their work) was going to benefit the Province of Nova Scotia by having a mine.

Joe: Yes, and it did, in the short term it did. And it made for a lot of jobs in a very rural area lacking in economic opportunities.

Jeannette: It employed a lot of people.

Joe: By pumping out the 1930’s mine, they were trying to attract private companies to come in and finish what was left in the ‘30s and “the private money” obviously didn’t see enough excuse to invest the first money. The first money would have been to pump the mine out. So that was Messervey’s whole idea as a high level government overseer - if we have this group of people who work for us - they ‘re trained - they know what they are doing; they can do it as cheaply and as effectively as anybody and we can send them to Stirling for a start. There were other places they worked. I think Stirling was the biggest and most prominent. They pumped the mine out. It goes back to the puzzle. You have all these reports, and they tell you what someone thinks is under there, but you don’t really know what’s under there. And in the Stirling case, there was a Glory Hole, and if you had scuba tanks you could swim through it but you still couldn’t see what was going on there. And, you don’t really trust reports because the industry is driven by big money, so reports are often exaggerated.

Joe: The government invested a certain amount of money to pump that mine out and they proved Messervey’s story. They pumped the mine out, Dome came in, cataloged what they could see, and they decided to open the mine, making a lot of jobs; that’s the game from the public’s point of view -jobs.

Jeanette: So, their interest in that was getting people working.

Jeanette: On my interview page, there’s one letter from a McCrea fellow. He met up with my brother. He was an Engineer. His father was the president of Dome Petroleum. So, he talks about the Talc and a lot of other stuff and his brother did a thesis as well. You might find that interesting story.

The Glory Hole/Glory Rock

Jeanette: About the Glory hole, was it something that was excavated in the 20’s?. Was it a shaft that collapsed?

Joe: Not a shaft. It was a ceiling collapsed. They got too close to the surface above a stope.

Joe: You have a picture of the Glory hole pumped out. I have a picture somewhere that shows a fissure, it’s a slit. It must have been just after they broke through the thing,. It’s a long slit in the ground with a wooden fence around it. That would be from back in the 20’s or 30’s. Then, my understanding was, they brought in a steam shovel in the ‘50s and that’s and that’s what took the thing from being a little slit of a roof collapse to this huge, much bigger hole. They did that with a steam shovel.

Jeanette: Why were they digging into that?

Joe: That was the richest stuff. It’s called a Glory Hole for a reason. That was the richest stuff there was. And that’s why they would have taken it - you have to think about these guys climbing up from below on wooden scaffolding, picking away at rock, drilling rock. I mean it was back in the 30’s; it wasn’t good conditions. It would have been horrible conditions. They would have had a waterfall raining on them straight time. And why are they doing it, because the rock is so rich you can’t help but take it. It’s Glory rock. And they went a little too far and the roof of the cathedral collapsed on them. And, maybe somebody gets hurt, and maybe somebody dies, but there’s a hole through to the sky.

There likely a similar situation, if you go on the land south of the Glory Hole and the Shaft 1. There was an old woods road and beside that, there was a collapse too. When you walk to the Southern and you look west of this southern bound log road, there’s a depression, presumably, a collapse. When they mined a little bit in that direction, they again got a little too close to the ceiling and that’s likely what that collapse is. Nobody’s been underground since to verify that but that’s most likely what that is.

Joe: I was trying to find these Glory spots, of surface ore, that were identified on some of the old maps. What they would have done, at some point early on – they were constantly walking the site. The original discovery was in the creek; there was a copper showing in the creek. And then, as time went on, they mapped near by going out further and further, 15 meters, 50 meters, 100 meters. They would have mapped other places- there’d be people digging holes by hand and finding rock of some value. And that’s how you start a mine project. You expose everything you can at surface, because it is a whole lot cheaper than exposing it underground. So, they walked around, and they exposed these spots, these isolated spots, of really good stuff at the surface. Because I didn’t have machinery to play with, I was trying to locate things that I could expose by shovelling by hand and I found one or two of them. We’re talking about stuff that is 30% metal. That’s just unbelievably rich rock. These days base metal ore would run 3% metal or something like that, so you’re talking about something that is 10X’s richer. That’s amazingly rich rock so, I was spending time up there, trying to find buried treasure. And I thought it was going to put money in my pocket. It didn’t, but that was some of the dream, as well.

The Tailings Pond

Joe: There was a company “Seabright” that was there in the 70’s. They catalogued the tailings pond. They surveyed the tailings pond, and took samples on a grid laid out on the tailings pond, and produced a report that said that there was this much metal, this much gold, in the tailings pond to be recovered. From that report, it’s been believed ever since, there’s 20,000 ounces of gold in those tailings. And where did those tailings come from? Richardson told me they didn’t flatten the ground, that that was too much hard work for no gain. They just ran their tailings out over the natural landscape, and the tailings would have been coming, in their case, out of another pipe that came out from the mill. One way of trapping metal is from the ground up ore. They use chemicals to grab on to the good stuff. And the waste, the tailings, is fluid, and it can be pumped through a pipe. They had created this earthen dam around an area they thought would be big enough to hold the tailings that would be produced, and they ran the pipe into the side of that. It would have been on the Western side of the currently existing tailings pond.

The old mill(1920s/1930’) didn’t have a tailings pond - that was ‘the bad old days’; they didn’t attempt to protect the ground at all. So, they pumped directly into the brook and that’s what killed all the vegetation along the brook because those tailings are very high in acid. And I was told by somebody local, that it killed everything for quite a way downstream. ‘Old ways” aren’t necessarily good – or, best.

Jeanette: Yes, that brook - it’s called Strachan’s brook. It goes all the way down though Framboise, crosses the road twice. It passes through land once owned by Strachan’s (thus the name) before going into the Framboise River which empties into the Ocean. It killed all the vegetation all the way down. When I was a kid there was a vast area of sand where it crossed the Barron road (aka Three Rivers road).

In the 50’s they made the tailings pond. If it rained a lot the water could flow into the river, so they had a culvert there. It was supposed to settle, (and the excess water would drain into the brook) but over the years the sediment ended up getting under the culvert and going into the brook, until 20 years ago then the government did another project there. Click here novascotia.ca/natr/meb/data/pubs/ofr_me_1996-016.pdf to view this project.

Joe: I was told, the last time I was there, by somebody local, that he had seen the first sign of green, starting to grow back. Between the tailings pond and the ocean. It took 50 years– the acid had been diluted enough that finally something could grow.

Joe: To me it’s a horror story in one sense but in the other sense 50 years in the history of this planet isn’t very long. It's only taken fifty years for all the poisons/toxins. that went into that brook, to be neutralized. There was a certain amount of talc and limestone with the ore, and Limestone and talc would neutralize the very acid metal minerals that contained the metal.

Jeanette: And same with the tailings pond, all that stuff is there, still. There’s still lots of chemicals in that stuff. Anyways, it’s not gone but it is contained for the most part.

Joe: It’s contained. That’s a good way of thinking of it. And sunlight, time and neutralizers go to work. I can take some hopefulness from that.

I give Jeanette Strachan permission to use the above information in part or in whole, online or in print If for publication I retain the right to review again the material to be used and the nature of the publication.

Signed by Joe Richman on May 30/20 with the above condictions.